Andalusia: A Melting Pot of Cultures

The history of Andalusia is a mosaic of cultures and civilizations dating back over 40,000 years.

Dear reader,

You know how much I love sharing my knowledge about my land with you. That’s why I want to invite you to keep discovering the stories full of life, mystery, and tradition that I share in my newsletter.

And now, let me take you on a journey through my beloved Andalucía.

One of the things I love most is seeing the surprise on everyone's face when they discover the historical and cultural richness of Andalusia. That’s why I want to dedicate this month’s article to giving a brief overview of the different historical periods of this region, along with examples of must-visit places that leave us in awe. Because Andalusia is one of the best places in the world to understand that a rich culture is the result of all those that have passed through it, leaving behind an incredible legacy.

Andalusia has always been a land of diversity, a place where cultures have met, exchanged ideas, and shaped unique styles, gastronomy, traditions, and craftsmanship. That’s why Andalusia is made up of many different "Andalusias"—each province distinct from the others. The customs, traditions, and architecture of Huelva or Cádiz are very different from those of Almería or Granada. Even neighboring cities like Seville and Córdoba, or Málaga’s coastline compared to Jaén, have their own unique character. We are not the same, and that makes us even greater.

The history of Andalusia is a mosaic of cultures and civilizations dating back over 40,000 years. Its legacy is reflected in more than 8,000 cataloged monuments and its rich cultural landscapes, making it one of the regions with the greatest historical heritage in Europe.

The First Inhabitants: From the Paleolithic to the Neolithic

40,000 years ago, Paleolithic hunters left their mark on Andalusia. The Cueva de la Pileta, in Málaga, is a testament to this period, with its cave paintings of bison and seals made using oxide pigments.

During the period we call the Neolithic, around 5000 BCE, the advent of agriculture led to the first settlements. One of the most remarkable is Los Millares, in Almería, considered the first fortified settlement in Europe, featuring stone walls and a sophisticated water channeling system. In Antequera, the Dolmens of Menga exhibit an astronomical alignment with a sacred mountain and the summer solstice, serving as both observatories and collective tombs where leaders were buried with ceramics and flint tools. (Here’s the link in case you missed the article I dedicated to it in January.)

Beyond these dolmens, there are many more, along with numerous Neolithic settlements scattered throughout the Andalusian region.

The Iberian Culture and Metallurgy

During the Iberian period, Andalusia became a metallurgical hub. Copper was extracted in Rio Tinto (Huelva) and silver in Aznalcóllar. One of the most remarkable discoveries is the Treasure of El Carambolo (Seville), consisting of 21 pieces of 24-carat gold, found in 1958.

In Cástulo, the Iberian capital, the Punic Tower from the 4th century BCE stands out. It is unique in the Iberian Peninsula for its decoration with Carthaginian funerary symbols known as Nefesh, demonstrating the fusion of Iberian and Eastern techniques.

Mediterranean colonizations left a profound mark on Andalusia. The Phoenicians, arriving from present-day Lebanon in 1100 BCE, established thriving trading ports such as Huelva, where they exchanged jewelry for minerals. In Huelva’s capital, beneath the Orden neighborhood, remains of a Phoenician trading port have been discovered, along with ceramics bearing inscriptions that have yet to be deciphered. The La Joya Necropolis, with its tholos-style tombs—circular burial chambers typical of the period—also belongs to this era.

Drawn initially by tuna fishing, the Phoenicians founded Gadir (modern-day Cádiz) in 1100 BCE. Near the Cathedral of Cádiz, remains of the ancient Phoenician port have been unearthed, including amphorae containing traces of garum, the famous fermented fish sauce exported across the Mediterranean.

Their yet-undeciphered script appears on stelae such as the Nora Stele, found in Cádiz and currently displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Seville.

The Phoenicians also founded Abdera, in present-day Adra, around 650 BCE. This port primarily focused on silver extraction, which was then exported across the Mediterranean.

The Tutugi Necropolis, in Galera, contains princely tombs filled with Phoenician grave goods, reflecting the significance of cultural and commercial exchanges in the region. Similarly, the Laurita Necropolis, in Almuñécar, has revealed Phoenician tombs adorned with Egyptian jewelry, scarabs, and Greek ceramics.

Although the Greeks had a lesser presence in the region, they also left their mark. In Vélez-Málaga, they founded Mainake, a Carthaginian settlement where coins bearing the image of Athena have been found—testimony to their influence in the area.

Rome and Baetica: The Empire’s Breadbasket

In 218 BCE, Rome began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, transforming Baetica (roughly modern-day Andalusia) into the Empire’s breadbasket. Cities like Itálica, birthplace of emperors Trajan and Hadrian, flourished with impressive mosaics and underground-heated baths. Baelo Claudia, a nearly intact Roman city, allows visitors to walk through its theater, forum, temples, and even public latrines. Acinipo, near Ronda, preserves a well-preserved Roman theater, while Córdoba, Seville, and Málaga hold numerous remnants of Roman influence.

The trade of Andalusian olive oil was so significant that in Rome, over 25 million amphorae bearing the Hispania Baetica seal accumulated at Monte Testaccio, serving as a testament to the vast production and export of this essential product for the empire’s economy.

Visigoths and Byzantines: A Lasting Mark on Our Heritage

With the fall of the Roman Empire, the Visigoths, a Germanic people, gradually conquered different parts of the Iberian Peninsula. In Andalusia, they left behind notable traces, such as the Basilica of Gerena in Seville, which features sarcophagi decorated with Visigothic chrismons (symbols of early Christianity). The Archaeological Crypt of Jaén’s Wall preserves remnants of a Visigothic fortification, while the Paleochristian Basilica of Vega del Mar holds tombs bearing early Christian symbols.

In Medina Sidonia, beneath Plaza de España, a Visigothic crypt contains repurposed capitals from earlier Roman structures. Meanwhile, the fortified complex of Recópolis is home to the only known Visigothic archaeological site in Andalusia with a cruciform church.

At the same time, the Mediterranean was undergoing significant shifts with the expansion of the Byzantine Empire from Constantinople. However, this period was about to change dramatically: in 711, the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. This rapid expansion ushered in Al-Andalus, an era that lasted for 800 years and left an indelible mark on Andalusia’s culture, architecture, and society.

Al-Andalus: 800 Years of Splendor

Al-Andalus went through three major stages:

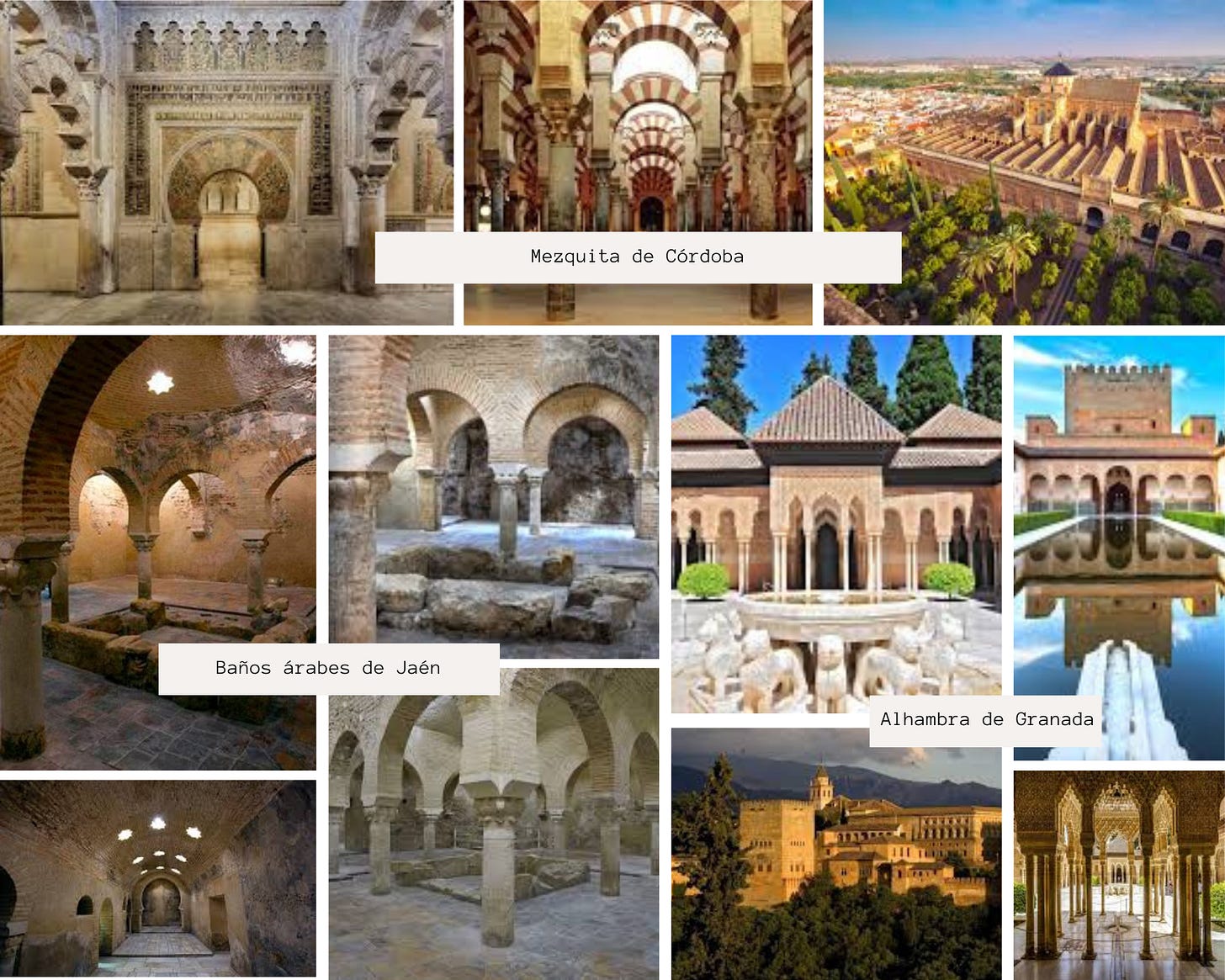

The Emirate and Caliphate of Córdoba (711-1031): In 711, the Muslims, in the name of the Caliphate of Damascus and under the Umayyad dynasty, began the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Córdoba became the capital and a major cultural and political center. During this period, emblematic monuments such as the Mosque of Córdoba and the palatial city of Medina Azahara were built. In the 11th century, a civil war known as the fitna led to the fragmentation of the caliphate into multiple taifas, which can be understood as city-states.

The Taifas and the Almoravid and Almohad Invasions (11th-13th centuries): After the disintegration of the Caliphate of Córdoba, the peninsula was divided into small taifas (city-states) that, although militarily weak, flourished culturally. During this period, the Arab baths (hammam) of Jaén and Granada were built. The arrival of the Almoravids from North Africa in the 11th century, and later the Almohads in the 12th century, once again unified Al-Andalus. Architectural examples from this period include the Torre del Oro and the Giralda in Seville, both of Almohad origin.

The Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238-1492): With the expansion of the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Portugal, and Aragon, only the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada managed to resist until 1492. During this period, architectural gems such as the Alhambra, the Alcazaba of Málaga and Almería, and numerous palaces in Granada were built.

In 1492, the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs marked the end of Al-Andalus and the beginning of the Westernization and Christianization of the territory. This period saw an overlap of architectural styles, blending the Andalusi heritage with the traditions of Queen Isabella's kingdom, Castile. Seville became a key port for trade with the Americas, and the Mudejar art style emerged—a fusion of Islamic and Christian influences—visible in the Royal Alcázars of Seville and many churches across the region.

This period was also crucial for the development of flamenco, born from the fusion of Sephardic, Castilian, Andalusi, and African music, along with rhythms brought from the Americas. In the 16th century, the Seville Artillery Factory was built, later becoming the Tabacalera. In Granada, the Royal Chapel stands out as one of the last examples of Gothic architecture, housing the tombs of the Catholic Monarchs, alongside the Castle of La Calahorra.

During the Golden Age and the Baroque period, Andalusia developed a distinctive style that combined Andalusi heritage with Renaissance reinterpretations. Examples of this Andalusian Baroque style can be seen in the Carthusian Monastery of Seville, the Church of La Magdalena, the Church of San Luis, and Écija, known as the "City of Towers" for its eleven Baroque bell towers. Other significant buildings include the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville, showcasing the region's rich artistic and cultural heritage.

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment marked milestones such as the San Fernando Observatory, where the meridian of Cádiz was calculated in 1793.

19th and 20th Centuries: Industrialization and Cultural Expansion

During this time, traditions such as bullfighting and flamenco became firmly established. The Plaza de Toros in Ronda, the oldest bullring in Spain, was built, and Málaga developed a strong steel industry, exemplified by the La Constancia Factory. This period also saw the boom of mining in Riotinto and the flourishing of the wine industry in Jerez, with the massive export of its famous sherry. Growing British investment in mining and industry left a significant mark on the region.

In the 20th century, Andalusia underwent a process of modernization with new urban and industrial developments, solidifying its status as a cultural and historical reference. Contemporary Andalusian architecture has drawn from its past while preserving its identity through figures such as Guillermo Vázquez Consuegra, Cruz y Ortiz, and Antonio Jiménez Torrecillas, who have reinterpreted the richness of Andalusia’s multicultural heritage in their works.

I hope you enjoyed this journey through our Andalusian history and culture.

Next week, I will talk about the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a lineage woven through power, the sea, and great expeditions. Sanlúcar de Barrameda, with its majestic palaces and the enigmatic tradition of “almadraba”, holds fascinating stories that have faded into the shadows of time. What secrets do these lands hide? How did they shape the history of Spain and the world?

If you want to uncover more about this history, power, and tradition, subscribe to my newsletter and join me on this journey. Subscribe to the newsletter.

Best regards,

Blanca.